Animals in a human world

She felt as though she had had a film removed from her eyes, and that she now saw clearly where before she had peered through a mist, or even not bothered to look.

(Lovat Dickson, Wilderness Man, The Amazing True Story of Grey Owl.)

We humans exploit, eat, commoditise, use and abuse millions of animals across the world. Despite the crucial roles many of these animals have played in the creation of our modern world, the stories of the animals themselves have usually gone unheard.

Today in a world that’s struggling with an environmental and ecological crisis, historians are starting to look again at our shared history. They’re beginning to take account of the parts played, usually unwillingly, by the animals.

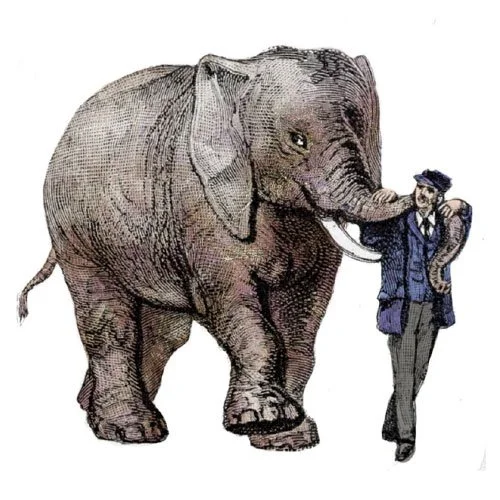

In my latest writing and illustration project I’m attempting to find ways to do the same.

It’s not easy. Truthfully and respectfully portraying the stories of the animals that have played a huge part in our recent human history, often seems to end up as a depressing catalogue of misery and torture. The scale and nature of the cruelty we have inflicted, and continue to inflict, upon the animals that share our world, is mind boggling.

Exploring the Victorian history of our human relationship with animals in the UK, reveals the huge numbers of wild animals that we destroyed, and we continue to destroy. Exploring our modern relationship with animals, reveals the industrial scale of the misery we now inflict on domesticated animals.

But looking at all this history and how we’ve reached the present situation, also reveals what we have lost as humans.

Up until the 1960’s children could still hunt for bird’s eggs in the UK and keep a wide range of pets, both domesticated and wild. Some of these children grew up to be the famous naturalists of today. Families bought meat from the butcher’s shop where animal carcasses hung in plain sight and children knew the origin of the meat on their plate. The family dog was often fed on scraps from the table. It might even live in a kennel outside or wander the streets during the day. It wasn’t called a ‘fur baby’ and made to live a life more suitable for a human child.

Today most animals that children come across are either humanised or mediated by books and TV. And as John Berger wrote, zoos are always a disappointment because we never experience the real animal. How can we, when we have them caged. Meeting a tiger on the loose would feel very different to meeting a tiger in a cage or in a wildlife documentary.

We have gradually alienated our children from the animal world and people increasingly have little real understanding of their own place in the natural scheme of things. The natural world has become something separate, a holiday destination if we’re lucky, a television documentary, a ‘fur-baby’ or a sanitised, pre-packed portion of meat.

So how can art and writing start to reflect a different relationship. How can we even begin to give a voice to the millions of animals that humanity has exploited and continues to exploit, and why bother?

The destructive power of the natural world, influenced by mankind, will destroy humanity eventually, yet we still imagine that we have the power to change this. We tell our children that it is up to them to save the planet, yet we don’t stop flying or give up eating meat or fish. Perhaps the only way our species will survive for much longer, is to understand and respect the importance of our relationship with all other living things. Perhaps by respecting the real stories of animals both past and present, we can start to respect the very life systems we all depend on.